COMMUNITY-LED ACCOUNTABILITY IN THE MINING SECTOR

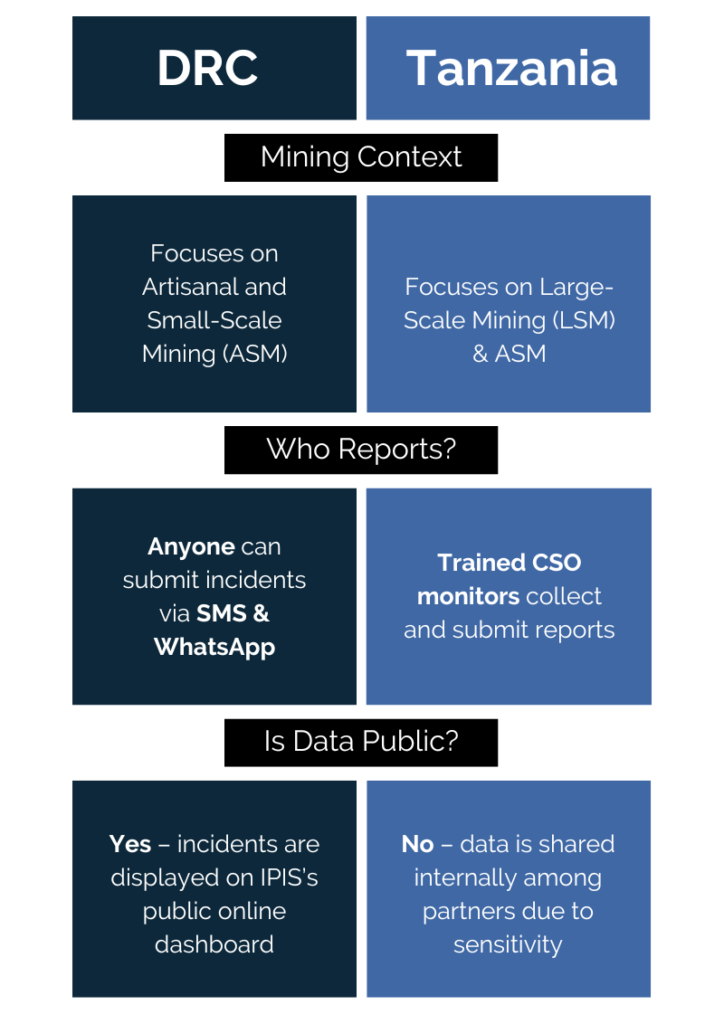

This case study examines the implementation of Kufatilia in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Kufuatilia in Tanzania – two related but distinct community-based incident monitoring systems developed by the International Peace Information Service (IPIS) to improve transparency, accountability and safety in the mining sector. While Kufatilia was first launched to support incident reporting and supply-chain due diligence in the DRC’s artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sector, Kufuatilia was later designed in Tanzania as an adapted model that responds to a different regulatory environment and stronger large-scale mining (LSM) presence. Together, the two systems illustrate how digital reporting tools and local civil-society partnerships can strengthen responsible mineral supply chains in diverse, and often conflict-affected, contexts. This study reviews the contextual differences, implementation approaches and observed impacts across both countries.

Context

Across Africa’s Great Lakes region, mineral extraction is closely tied to governance challenges, insecurity and human rights concerns. International frameworks such as the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas emphasise that companies have an ongoing responsibility to identify and address risks of harm within their supply chains.[i] However, practical implementation often remains limited. A 2020 assessment by the Responsible Mining Foundation found that “only about one-third of the [surveyed] mine sites showed evidence of operational-level grievance mechanisms for communities and workers”.[ii]

In these contexts, community-based and digital reporting systems have emerged as critical tools for bridging the gap between affected populations, companies and authorities. Systems like Kufatilia build on these principles, providing accessible channels for documenting incidents and strengthening dialogue in areas where state oversight is weak.

DRC: Artisanal mining, conflict and governance gaps

The Democratic Republic of the Congo holds vast natural wealth, including an estimated 750 tonnes of proven gold reserves and 700 million carats in diamond reserves.[iii] In eastern DRC alone, a 2020 IPIS study identified nearly 3,000 artisanal mine sites employing over 400,000 miners.[iv] However, artisanal and small-scale mining operates largely informally and without clear regulation, resulting in poor working conditions, exploitation and the persistence of conflict-linked supply chains. Gold, in particular, is the most extracted and trafficked mineral due to its high value-to-weight ratio, facilitating smuggling and fuelling regional insecurity. This deprives the DRC government of critical revenue and often leads to the financing of armed groups and local militias. Weak state presence in many mining areas has further complicated governance and enforcement. The absence of formal safety and reporting mechanisms has had severe consequences, with the Delve Database estimating that up to 2,000 ASM miners die annually in the DRC due to unsafe conditions.[v] In this context, civil society organisations play a key role in monitoring human rights and mediating between communities, authorities and private actors.

Tanzania: LSM and ASM dynamics, regulatory reforms and community challenges

While large-scale mining has brought infrastructure investment and formal employment, it has also created social and governance challenges. Communities raise concerns about environmental degradation, displacement, violence and limited benefit-sharing, while tensions emerge where ASM overlaps with industrial concessions.[vi] Persistent issues such as police corruption, inadequate grievance mechanisms and an overreliance on local authorities for dispute resolution further undermine community trust. These local structures, often under-resourced or perceived as partial, struggle to address complaints effectively. Furthermore, the involvement of the private security sector in protecting LSM operations adds a layer of complexity to the relationships between communities, companies and local authorities. Security personnel are implicated in community disputes and allegations of excessive force or intimidation, yet such incidents often go undocumented or unresolved.

Government reforms, including the 2017 amendments to the Mining Act and the creation of mineral trading centres, have sought to improve transparency and formalisation. However, the gap between national policy and local practice remains wide. In this context, community-based reporting systems play a vital role in offering residents an alternative channel for raising concerns, strengthening accountability and fostering dialogue between citizens, companies and authorities.

The Kufatilia systems

Kufatilia (DRC) and Kufuatilia (Tanzania) refer to two community-based monitoring systems developed by IPIS with support from the European Partnership for Responsible Minerals (EPRM). Although the names differ slightly, reflecting variations between Congolese and Tanzanian Swahili, both are derived from the verb “to track”. The first system, Kufatilia, was implemented in the DRC to enable community-driven incident reporting in ASM areas. A separate, adapted system – Kufuatilia – was later developed for Tanzania to respond to that country’s distinct governance frameworks and the monitoring needs of both ASM communities and regions influenced by LSM.

DRC: The Kufatilia reporting system

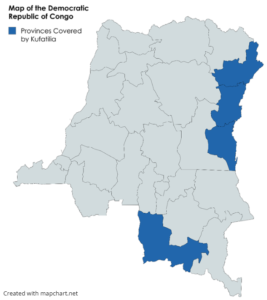

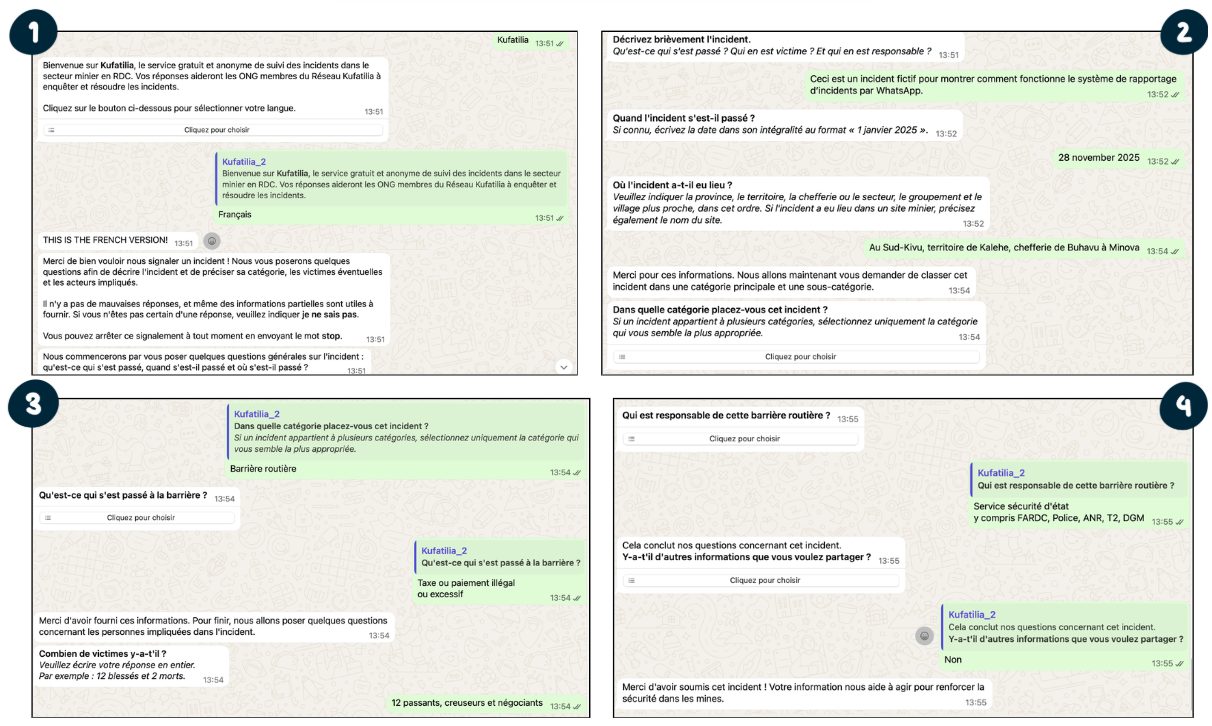

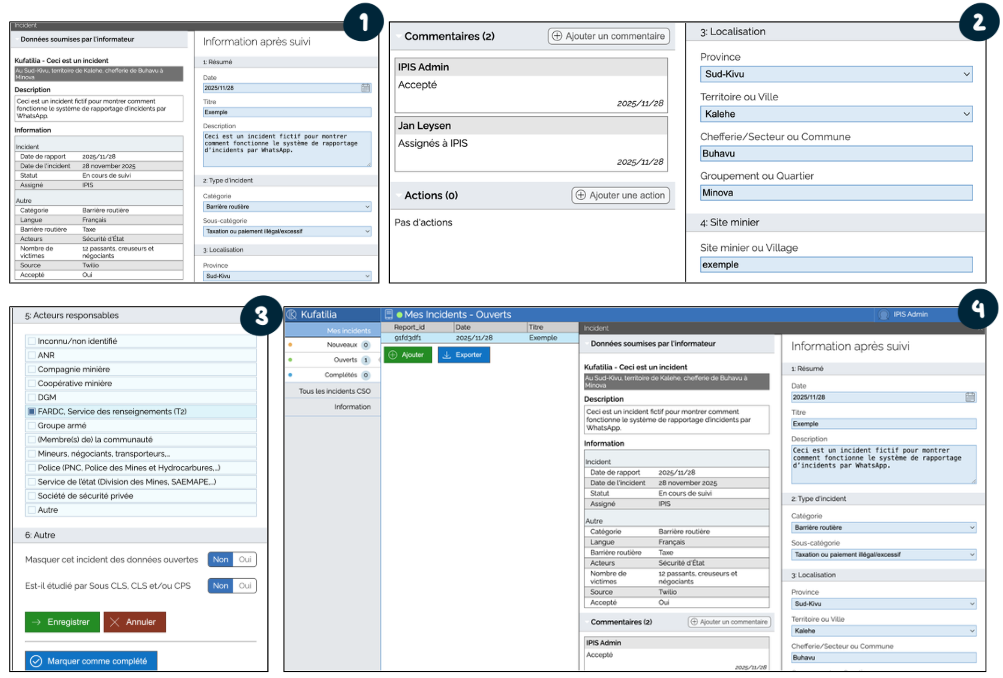

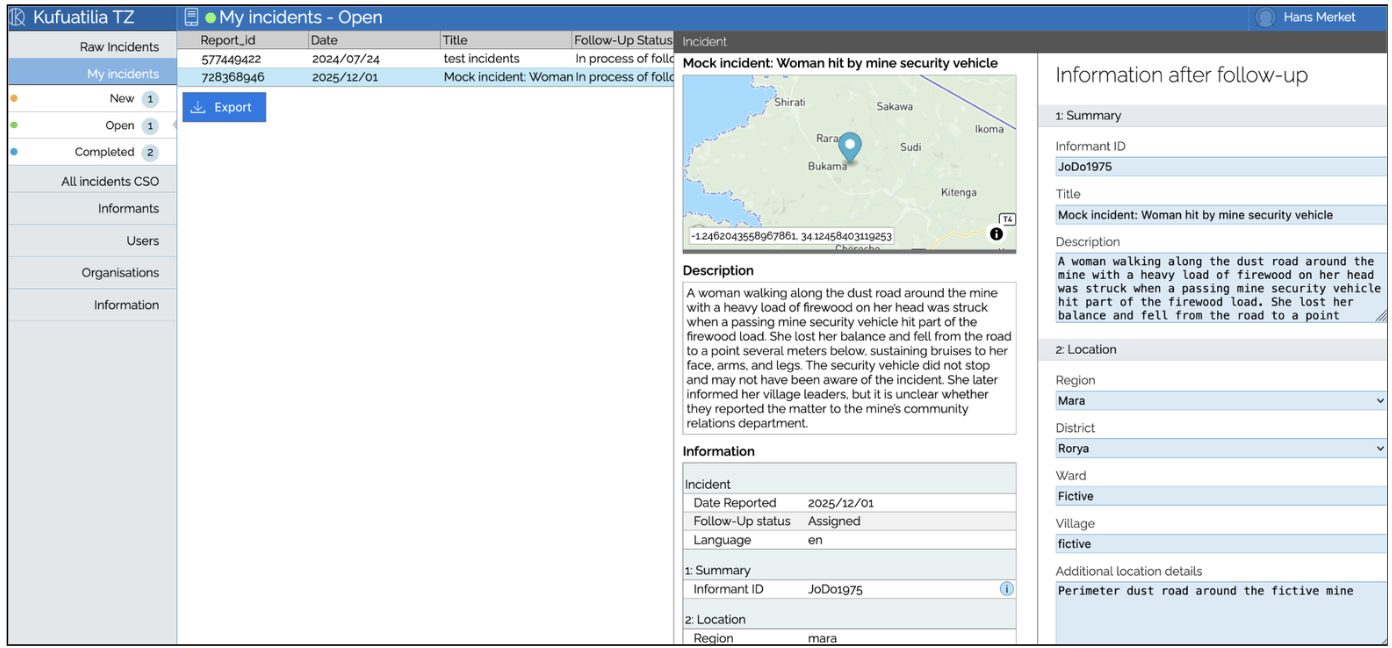

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kufatilia operates as a free, anonymous SMS and WhatsApp-based system that allows community members in mining areas to report incidents directly to partner CSOs. By sending the keyword “Kufatilia” to one of the three designated phone numbers, the informant receives an automated questionnaire that they complete through sequential SMS or WhatsApp messages [Figure 1]. Reports are subsequently verified and followed up by local CSOs, who may investigate, mediate with local authorities or aid depending on the nature of the case [Figure 2]. Incidents are categorised into the following: child labour, violence, mining accident, corruption or fraud, theft, roadblocks, conflict with a mining company, environmental problem and other [Figure 2]. Currently, 19 CSOs are partnered with Kufatilia across the Ituri, Lualaba, North-Kivu and South-Kivu provinces of the DRC.

To promote transparency and accountability, IPIS also maintains a public online dashboard that displays each verified incident and its follow-up status, accessible via this link.

IPIS is now strengthening Kufatilia through a formal CSO network and an internal follow-up platform that improve coordination and oversight of reported incidents. The platform enables partners to pool and track data, as well as identify recurring issues requiring collective advocacy. These developments mark a shift from a reporting tool to a collaborative system for response and prevention in the DRC ASM sector.

Tanzania: The Kufuatilia monitoring system

Tanzania: The Kufuatilia monitoring system

In 2024, IPIS expanded Kufatilia to Tanzania’s Shinyanga region, adapting the model to address challenges around LSM operations. Unlike in the DRC, where anyone can send a report via SMS or WhatsApp, incident documentation in Tanzania is carried out by trained monitors from local CSOs [Figure 3]. This approach reflects a more controlled reporting environment shaped by regulatory and security considerations.

By relying on trained monitors, IPIS has been able to standardise data collection and ensure higher-quality documentation of incidents, improving the reliability and comparability of reports. As of 2025, incidents are followed up by 4 partner CSOs in the Shinyanga and Mara regions of Tanzania.

Key differences between systems

Impact & next steps

Kufatilia’s impact in the DRC

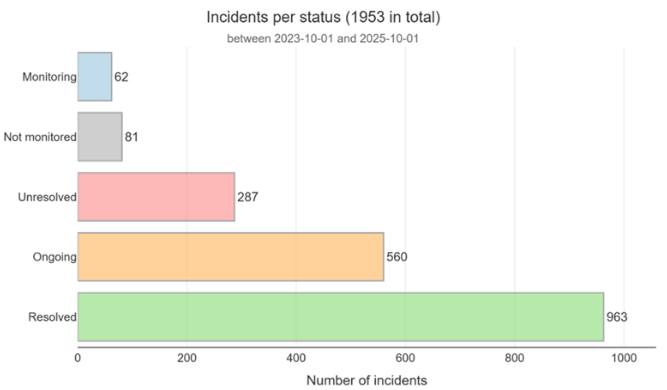

Since its launch in 2018, Kufatilia has documented more than 6,000 incidents across eastern DRC. Between October 2023 and October 2025 alone, 1,953 incidents were recorded, with 963 (~50%) marked as “resolved”. While definitions of resolution differ among civil society partners, the system has improved the visibility of local conflicts and helped channel cases to relevant authorities, companies or humanitarian actors.

The platform has built trust amongst individual miners and their communities who often fear retaliation or lack confidence in formal institutions. An external evaluation conducted in March of 2024 found that an Armed Forces of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (FARDC) Lieutenant known to be in collaboration with Nvatura and M23 armed groups was reported through Kufatilia and subsequently arrested. In the same report, CSO partners revealed that military personnel no longer dared to go on mining sites for fear of being reported through Kufatilia.

Kufatilia has also strengthened coordination among local CSOs, enabling joint advocacy around issues such as illegal taxation, security abuses and mine safety. The system’s data has also informed targeted investigations into recurring risks in the artisanal mining sector. One example is a study conducted by Action for Peace and Development (APDE), a Kufatilia partner CSO, in collaboration with IPIS, examining why so many incidents were being reported in Misisi, a key artisanal gold-mining area in South Kivu. The report, “Misisi: Why So Many Incidents in the Gold Supply Chain?”, [vii] drew on community incident reports and field research to highlight systemic issues such as unsafe mining conditions, mercury pollution, illegal taxation and the presence of armed groups.

Based on these findings, APDE and IPIS issued recommendations calling for the restoration of state authority, improved technical support for miners, safer environmental practices and youth employment initiatives to reduce the risk of recruitment into armed groups. This case demonstrates how the reporting mechanism can support evidence-based advocacy, helping local organisations and authorities identify structural governance challenges that extend beyond isolated incidents.

Despite these gains, IPIS continues to face several challenges in the DRC. Limited budgets and funding constraints complicate engagement with Congolese partners and local or provincial multi-stakeholder committees. Moreover, operating in conflict-affected provinces such as North and South Kivu presents persistent logistical and security difficulties that hinder the consistent functioning of Kufatilia. Nonetheless, the system remains an essential tool for community oversight and accountability within the artisanal mining sector.

Kufuatilia’s impact in Tanzania

Kufatilia’s 2024 expansion into Tanzania saw the evolution of Kufatilia from informal ASM settings to large-scale industrial mining (LSM) contexts. By training incident reporters from local CSOs in Shinyanga and neighbouring regions, IPIS has prioritised data quality and security

Though still in its second year, the Tanzanian implementation has already encouraged stronger partnerships between community-based organisations and large mining companies. IPIS programme staff note that partner CSOs have begun supporting local residents who submitted grievances through company complaint systems and during compensation processes related to land acquisition or damage caused by mining activities. This improved monitoring of impacts and grievances has, in turn, contributed to greater awareness among mining companies of the risks and community concerns associated with their operations.

Kufuatilia also addresses challenges in the private security sector, an area of growing concern in large-scale mining contexts where accountability mechanisms remain limited. According to local partners, the platform has strengthened both responsiveness and credibility in community advocacy. As Jonathan Kifunda of Thubutu Africa Initiatives (TAI) observed, “Kufuatilia has brought us closer to the communities we support. The system fosters a sense of ownership, empowering people to take action for justice within their own communities”.[viii]

Like its counterpart in the DRC, IPIS has faced challenges in the implementation and operation of Kufuatilia in Tanzania. Mainly, the system has dealt with difficulty in maintaining engagement with monitors and ensuring incident reports include all relevant information for follow-up. These roadblocks speak to the persistence of IPIS in maintaining operations under challenging conditions and its ongoing efforts to strengthen the quality and consistency of its data.

Next steps for Kufatilia

In the DRC, IPIS aims to strengthen the existing CSO network and build closer collaborations with government agencies, companies and other partners to improve coordination and incident resolution. In Tanzania, the focus will be on supporting partners to independently analyse incidents and develop strategic responses, ensuring that local actors can use data for advocacy and dialogue. Ultimately, IPIS envisions Kufatilia as both a reporting mechanism and a capacity-strengthening network for local civil societies, moving beyond incident response towards long-term prevention and systemic change.

Recommendations

For organisations and donors supporting responsible mining initiatives, the following recommendations are proposed:

- Invest in local CSO capacity: Sustainable incident monitoring depends on trained and trusted community partners. Support should prioritise skills development, digital literacy and financial independence of CSOs.

- Support the development of shared standards for incident resolution: Encourage and fund collaborative efforts among implementing partners to define clear resolution criteria and metrics. This will strengthen data comparability and credibility across programmes.

- Enhance synergies with government agencies and regional bodies: Building bridges between the Kufatilia work and governmental actors will enhance accountability, policy alignment and lesson learning without compromising community trust.

- Adapt technology to local governance realities: Contextual flexibility, such as SMS in DRC vs. CSO-led reporting in Tanzania, should remain a core design principle.

Conclusion

Kufatilia demonstrates how locally grounded, digital monitoring systems can bridge the gap between communities and governance structures in resource-rich but fragile environments. Its evolution from an SMS and WhatsApp-based tool in the DRC to a structured CSO-led mechanism in Tanzania underscores the importance of adaptability, trust-building and partnership in scaling responsible mining practices.

As IPIS continues to refine and expand the two systems, Kufatilia stands as a promising model for rights-based, community-driven accountability in the extractive minerals sector – one that aligns with global due diligence standards while responding to the lived realities of miners and their communities.

Sources

Unless otherwise cited, information in this case study regarding the Kufatilia programme design, implementation and operations is drawn from the International Peace Information Service (IPIS) project page[ix] and from personal communications with IPIS programme staff in 2025.

[i] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2016). Due diligence guidance for responsible supply chains of minerals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas (3rd ed.). OECD Publishing. https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/OECD-Due-Diligence-Guidance-Minerals-Edition3.pdf

[ii] Responsible Mining Foundation. (2020). Harmful impacts report. Responsible Mining Foundation. https://www.responsibleminingfoundation.org/app/uploads/RMF_Harmful_Impacts_Report_EN.pdf

[iii] United Nations Economic Commission for Africa. (n.d.). Democratic Republic of Congo — ASM profile [Web page]. https://knowledge.uneca.org/ASM/drc

[iv] International Peace Information Service (IPIS). (2020). Delve country profile: Democratic Republic of Congo. Delve Database. https://www.delvedatabase.org/uploads/resources/Delve-Country-Profile-DRC.pdf

[v] Delve. (2022). How unsafe is ASM? Counting and contextualizing fatality frequency rates. Delve Database. https://www.delvedatabase.org/resources/how-unsafe-is-asm-counting-and-contextualizing-fatality-frequency-rates

[vi] Merket, H. (2019, September 25). As Tanzania confronts its industrial miners, what do locals think? African Arguments. https://africanarguments.org/2019/09/as-tanzania-confronts-its-industrial-miners-what-do-locals-think/

[vii] Action pour la paix et le développement (APDE). (2019, October). Misisi, pourquoi tant d’incidents dans la chaîne d’approvisionnement de l’or? [Misisi, why so many incidents in the gold supply chain?]. International Peace Information Service. https://ipisresearch.be/publication/voix-du-congo-misisi-pourquoi-tant-dincidents-dans-la-chaine-dapprovisionnement-de-lor/

[viii] International Peace Information Service. (2025, April 2). KUFUATILIA expands to Tanzania: Strengthening civil society monitoring and community support in the mining sector. IPIS. https://ipisresearch.be/kufuatilia-expands-to-tanzania-strengthening-civil-society-monitoring-and-community-support-in-the-mining-sector/

[ix] International Peace Information Service (IPIS). (n.d.). Kufatilia: Incident reporting and monitoring. https://ipisresearch.be/project/kufatilia-incident-reporting-and-monitoring/

Disclaimer

As per the Disclaimer on the homepage, neither the International Code of Conduct Association nor any authors can be identified with any opinions expressed in the text of or sources included in The International Code of Conduct Case Map.