Contexte

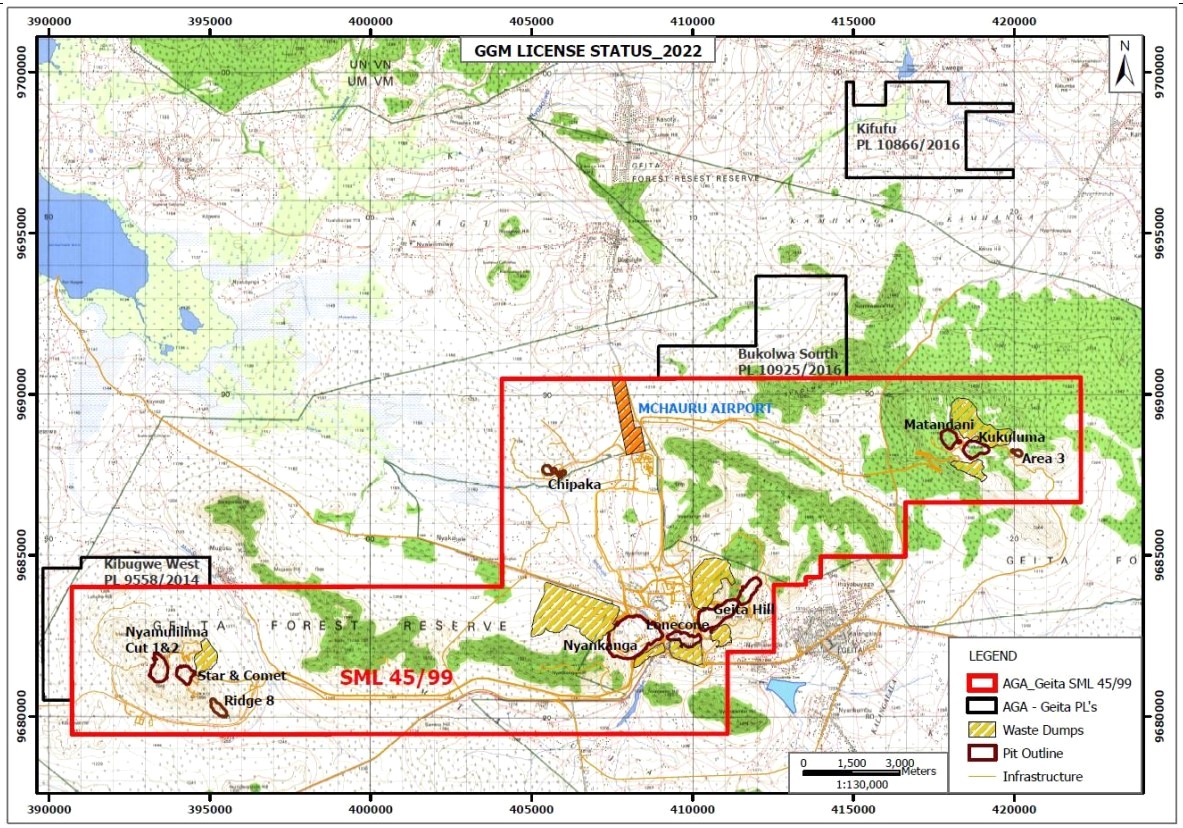

La mine d’or de Geita (GGM) est située dans les champs aurifères du lac Victoria en Tanzanie, à environ 120 km de la ville de Mwanza et à 4 km à l’ouest de la commune de Geita. La population de Geita est d’environ 1,7 million de personnes, avec des activités économiques variées, notamment des travaux miniers artisanaux et à petite échelle, l’élevage et l’agriculture de subsistance. GGM est l’une des plus importantes exploitations minières d’or en Afrique de l’Est. La concession s’étend sur 196,27 km2 et comprend une forêt dense et des collines. Elle est exploitée en tant que mine à grande échelle depuis 2000, mais l’exploitation minière a lieu dans la région depuis les années 1930. En 1999, Ashanti Goldfields Company Limited a acquis la mine et, en 2004, la société sud-africaine AngloGold Limited a racheté Ashanti, créant ainsi AngloGold Ashanti (AGA), qui a ensuite pris le contrôle de GGM. Depuis, la mine est devenue un acteur essentiel du secteur minier tanzanien, contribuant de manière significative à la production d’or du pays. La mine emploie environ 6 800 personnes, y compris les sous-traitants, dont le contingent de sécurité privée. Environ 90 % des personnes employées par la mine sont issues de la communauté locale.

GGM est une exploitation minière à ciel ouvert et souterraine, qui extrait de l’or de différents gisements. La mine a toujours affiché des niveaux de production impressionnants, ce qui en fait un atout économique vital pour la Tanzanie.

La sécurité à GGM est d’une importance capitale en raison de la valeur élevée du métal précieux qui y est extrait. La concession couvre une vaste zone, avec des villages à l’intérieur et à la périphérie. Environ 75 % de la concession minière se trouve dans la réserve forestière de Geita, qui est typiquement dominée par la forêt de Miombo. Il n’y a pas de barrière physique à la limite de la mine.

Les relations avec la communauté locale n’ont pas toujours été faciles. Avant 2014, la sécurité était assurée de manière traditionnelle, en s’appuyant fortement sur la police et sur l’utilisation de la force ou de la menace de force à des fins de dissuasion et d’application de la loi. Les incursions étaient fréquentes et les incidents graves courants.

Depuis 2014, la mine a mis en place un dispositif de sécurité innovant, complet et intégré pour protéger son personnel, ses biens et l’or extrait, sous la forme d’une stratégie révisée très attendue appelée « Plan en cinq points – Sécurité renforcée de la communauté », qui, en résumé, repose sur les éléments suivants:

- Éloigner les personnes des risques et les risques des personnes, afin de réduire les risques de conflit.

2. Définir le rôle des communautés en complément des initiatives de sécurité.

3. Définir le rôle de la sécurité privée et publique dans le soutien de l’approche de la sécurité renforcée par la communauté.

4. Utilisation d’équipes de réaction rapide formées, qualifiées et équipées pour améliorer la réponse et le traitement des incidents.

5. Optimisation de la technologie par rapport à la main-d’œuvre – utilisation accrue des technologies appropriées pour réduire les risques et améliorer l’efficacité.

Ces dispositions comprennent une combinaison de protection virtuelle du périmètre, de mesures de sécurité physique, de systèmes de surveillance avancés, de personnel de sécurité privé et interne sous contrat bien formé et de la police. En outre, depuis 2017, des membres de la communauté ont été recrutés à la fois dans la concession et dans la zone environnante et sont employés dans des rôles de « police communautaire ». Des zones d’accès restreint sont établies pour contrôler l’entrée dans les zones critiques, et des technologies de surveillance modernes, telles que des caméras thermiques de vidéosurveillance et des capteurs, sont déployées stratégiquement sur l’ensemble du site et dans le périmètre pour surveiller les activités en temps réel à partir d’un centre de contrôle de sécurité centralisé, ce qui permet une réponse coordonnée contre les menaces détectées.

Pour garantir la sécurité de la main-d’œuvre, la mine d’or de Geita a mis en place des protocoles de sécurité et des plans d’intervention d’urgence très stricts. Des simulations et des séances de formation sont régulièrement organisées pour préparer le personnel à divers scénarios, y compris des accidents et des menaces potentielles pour la sécurité.

Outre ses contributions économiques, la mine d’or de Geita a également joué un rôle dans les initiatives de développement communautaire. La mine investit dans des projets d’éducation, de soins de santé et d’infrastructure dans les communautés environnantes, contribuant ainsi au bien-être général de la région. Parallèlement aux dispositifs de sécurité intégrés, ces initiatives de développement ont contribué à améliorer les relations avec les communautés.

Grâce à un dispositif de sécurité solide et innovant qui comprend à la fois un dispositif de police de proximité et des services de sécurité privée responsables, la mine assure non seulement la protection de ses précieuses ressources, mais favorise également un environnement sûr et prospère pour sa main-d’œuvre et les communautés avoisinantes.

L’environnement de Sécurité : Du conflit à l’implication de la communauté

Dans le passé, la sécurité à GGM a connu des difficultés majeures, avec des taux élevés d’incursions et d’incidents, d’invasions de puits, de vols et de collusions. En conséquence, le nombre de blessures subies par le personnel de sécurité, ainsi que les blessures et les décès de tiers, ont augmenté. La dégradation générale des relations avec la communauté a également entraîné des perturbations dans les activités de l’entreprise. Ces problèmes se sont poursuivis à un rythme soutenu entre 2010 et 2015, les incursions atteignant un pic de 15 000 personnes au cours d’une semaine particulière en 2015.

Des exploitations minières artisanales et communautaires sont présentes dans les environs. La population de Geita a considérablement augmenté au cours des vingt dernières années, des centaines de milliers de personnes ayant été attirées dans la région par l’attrait de l’or. Il existe deux zones d’exploitation minière communautaire dans la concession, qui sont actives. Plutôt que d’essayer de fermer ces zones, AGA coexiste avec ces communautés. La concession est également un territoire forestier protégé. L’élevage et la garde de troupeaux sont très répandus dans la région. Cela peut également être une source de conflit car les éleveurs traversent illégalement la concession et la zone forestière protégée.

Avant 2014, le recours à la force ou à la menace de la force était le principal outil utilisé pour lutter contre les incursions sur le site. Il est toutefois apparu clairement que cette stratégie n’était pas efficace et qu’elle exacerbait les relations déjà difficiles avec la communauté environnante.

Comme le montre le graphique ci-dessous, les incursions dans la concession ont considérablement diminué au cours des dix dernières années grâce à la mise en œuvre du « Plan en cinq points – renforcement de la sécurité de la communauté ».

En tant que membre de l’initiative des Principes volontaires sur la sécurité et les droits de l’homme (PVSDH), AGA signale les incidents de sécurité sur une base annuelle. Les données pour 2021 et 2022 pour ses mines basées en Afrique, y compris Geita, sont ci-dessous.

Les sept secrets de la réussite

De nombreux facteurs ont contribué à une relation plus harmonieuse entre la mine et la communauté environnante. Le dispositif de sécurité innovant a sans aucun doute joué un rôle clé, associé à des programmes de développement communautaire équitables. Sept facteurs, décrits plus en détail ci-dessous, ont été déterminants. Les cinq premiers sont les éléments qui composent le dispositif de sécurité intégré sur le site. Les deux derniers sont liés à la culture d’entreprise plus large d’AGA chez GGM.

- Sécurité interne – Leadership engagé et innovant

2. Sécurité privée – Passer un contrat avec un prestataire responsable

3. Police – Principes volontaires sur la sécurité et les droits de l’homme

4. Police de proximité – Intégrale à la sécurité et aux relations avec la communauté

5. Utilisation de la technologie – Sécurité sans frontières

6. RSE – Investissement dans la communauté

7. Culture d’entreprise – alignement sur les valeurs

1. Sécurité interne – Leadership engagé et innovant

Le responsable mondial de la sécurité d’AGA a joué un rôle déterminant dans la direction de l’équipe de sécurité de GGM. En tant que membre de l’équipe de direction de la durabilité de l’entreprise, son travail dans le cadre des fonctions de durabilité lui a permis d’apprécier le rôle important que l’engagement communautaire profond peut et doit jouer dans les opérations quotidiennes de l’organisation. C’est sans doute l’une des raisons pour lesquelles l’équipe de sécurité de GGM ne travaille pas de manière isolée, mais collabore avec d’autres fonctions pour assurer la sécurité de toutes les personnes (internes et externes).

L’équipe de sécurité de GGM, composée presque exclusivement de Tanzaniens et de locaux, possède les connaissances locales et l’expérience pratique nécessaires pour tester et développer ce que certains pourraient considérer comme un dispositif de sécurité intégré peu orthodoxe. Le responsable principal de la sécurité à la mine a été recruté localement dans la communauté de Mara, mais il vit à Geita depuis l’âge de la scolarité et a gravi les échelons de l’entreprise, ayant commencé comme agent de sécurité. Il est à la fois très expérimenté et exceptionnellement compétent.

Il a fait l’expérience directe des lacunes des approches traditionnelles en matière de sécurité, où l’usage de la force et la dissuasion par la démonstration de l’usage de la force étaient les principaux outils utilisés. Selon lui, la première victoire rapide sur le site a été de mettre fin à l’utilisation de balles réelles par tous les prestataires de services de sécurité sur le site (privés et publics) et d’imposer le respect du continuum de l’utilisation de la force. Tout le personnel de sécurité travaillant dans la concession doit obligatoirement suivre une formation aux droits de l’homme et aux principes volontaires sur la sécurité et les droits de l’homme (PVSDH). Cette exigence d’intégrer la formation aux droits de l’homme dans les opérations de sécurité, formulée par AGA, a eu des effets positifs significatifs.

En 2016, le responsable principal de la sécurité de GGM, sous la direction du responsable mondial de la sécurité d’AGA, a testé un modèle de police de proximité. Une fois que son succès a été manifeste, le programme a été étendu à l’ensemble du site. Le directeur principal de la sécurité a pleinement adopté le modèle de police de proximité, déclarant que l’objectif du programme n’est pas de lutter contre les criminels, mais plutôt de partager plus équitablement les bénéfices d’AGA au sein de la communauté : « Tout le monde doit pouvoir bénéficier des fruits de la GMG ». Le responsable de la sécurité a suivi les directives de la direction de l’entreprise, les a mises en œuvre et les a adaptées au contexte local.

À GGM, la sécurité est intégrée à chaque décision, le responsable principal de la sécurité étant un membre de confiance de l’équipe de direction du site, régulièrement consulté pour obtenir des conseils sur les questions sociales et de sécurité et avant l’élaboration de tout projet. La sécurité est donc intégrée dans chaque plan de projet, introduite et appliquée en tant que concept de « responsabilité partagée » dans les processus opérationnels quotidiens. Cela permet d’éviter que la sécurité ne devienne une réflexion après coup.

De même, le chef de l’unité de police de proximité de GGM est membre de l’équipe de sécurité interne de haut niveau. Ancien officier de police, il s’est intégré dans les communautés où le projet est mis en œuvre, étant à la fois connu et respecté par elles. Il est impliqué tout au long du processus de recrutement et de formation et siège au comité directeur du projet. Ayant fait la transition entre la police publique et l’équipe de sécurité interne de GGM, il est également connu et respecté par la police, qui a la responsabilité et le commandement ultimes du programme.

L’équipe de sécurité interne compte 195 personnes à plein temps. La sécurité est assurée à la fois dans les mines à ciel ouvert et dans les mines souterraines. Il existe une division interne spéciale au sein du service de sécurité interne qui assure une sécurité souterraine spécialisée. Des coordinateurs d’équipe sont chargés des opérations sur le terrain.

Dans la vidéo ci-dessous, le responsable principal de la sécurité de GGM nous fait part de ses observations sur les points suivants :

L’histoire de la sécurité chez GGM ;

L’évolution de l’approche de l’entreprise en matière de sécurité sur le site, y compris le développement d’un programme de police de proximité en tant qu’élément essentiel d’une approche intégrée ;

L’utilisation de la technologie pour la sécurité.

Suleiman Machira, Directeur de la Sécurité, GGML

Recommandations

- Permettre au personnel de sécurité de haut niveau de bénéficier d’une expérience plus large en matière de relations avec la communauté au sein de l’organisation.

- Promouvoir des talents locaux expérimentés à des postes de sécurité de haut niveau. Cela permet de s’assurer que les dispositifs de sécurité sont bien adaptés aux contextes locaux et d’instaurer la confiance avec les communautés locales.

- Recruter des candidats compétents au sein de la police publique permet de jeter des ponts vers les forces de sécurité publique.

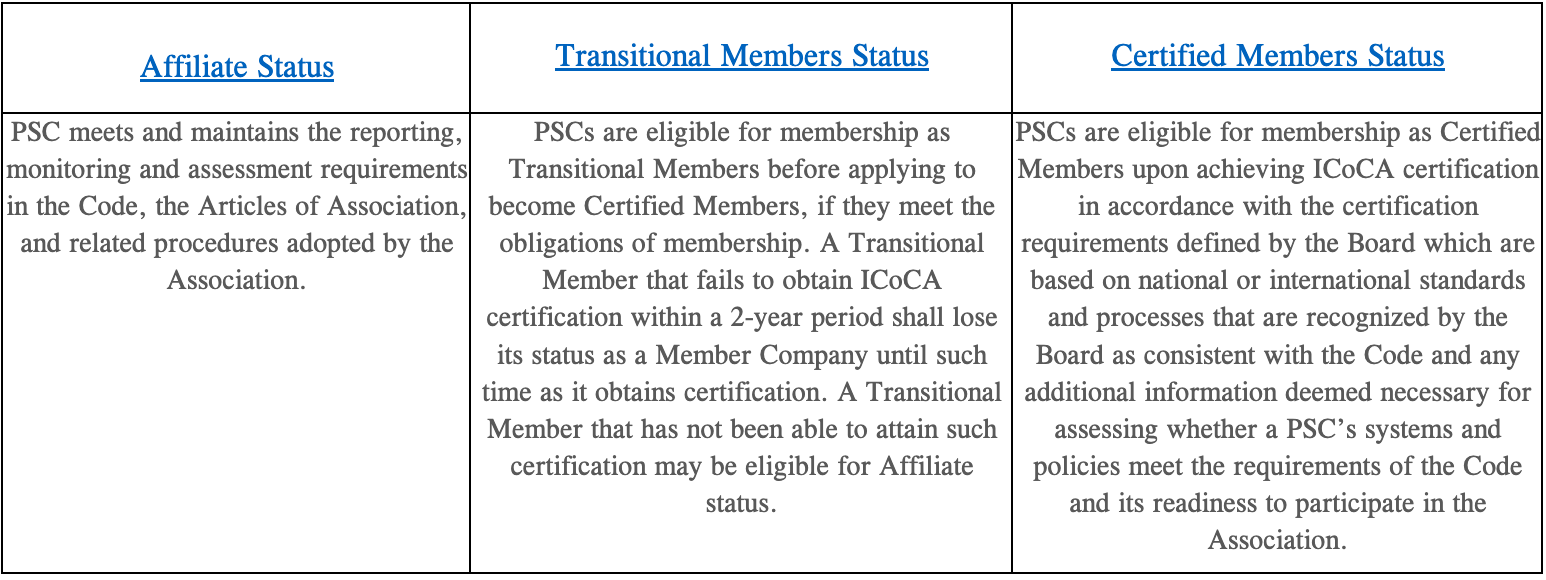

2. Sécurité privée : Passer un contrat avec un prestataire responsable

En 2018, GGM a passé un contrat avec SGA Security, une entreprise certifiée ICoCA. D’autres entreprises de sécurité privées sous-traitantes opèrent autour du site et leurs contrats ne sont pas directement conclus avec GGM. La principale entreprise sous-traitante est GardaWorld, une autre entreprise certifiée ICoCA, qui assure la sécurité de l’entreprise de forage contractante. SGA Security dispose de 700 personnes sur le site de GGM lorsqu’il est au complet. Les gardes sont répartis entre ceux qui ne sont pas armés et ceux qui sont équipés d’armes moins létales (pas de munitions réelles).

SGA Security – Le point de vue du chef d’entreprise

SGA Security a repris le contrat de GGM en 2018. La direction de SGA Security savait qu’il s’agirait d’un contrat difficile compte tenu de l’histoire problématique de la mine. Les intrusions ont diminué de plus de 80% depuis qu’ils ont repris le contrat et SGA a été un contributeur clé. Du point de vue du directeur général, l’un des secrets de la réussite réside dans le fait qu’avant d’être déployé, le personnel de SGA reçoit une formation sur le respect des droits de l’homme. Des formations de remise à niveau sur ces questions sont organisées quotidiennement (voir l’entretien vidéo ci-dessous avec Edward Diswas). L’engagement des parties prenantes entre les quatre acteurs qui composent le dispositif de sécurité (sécurité interne, sécurité privée, police, police de proximité) a également été un facteur clé de réussite sur le site. La sécurité privée, ainsi que la police de proximité, constituent le contingent le plus important. Leur intégration et leur partenariat avec l’équipe de sécurité interne de GGM et la police se traduisent par une approche bien coordonnée avec le fournisseur de sécurité privée.

La gestion des incidents, le suivi et l’évaluation des performances ont été essentiels. Le service de sécurité de SGA a recours à des « tests de pénétration », c’est-à-dire qu’il crée intentionnellement une situation sans que le personnel testé sache qu’il est testé, afin de voir comment le personnel répond et réagit. En surveillant la réaction du personnel dans ces conditions contrôlées, ils sont en mesure de tirer des leçons qui sont partagées avec le(s) membre(s) du personnel qui a(ont) été surveillé(s) ainsi qu’avec l’ensemble de la force de garde. Pour tester l’usage minimal de la force, par exemple, ils peuvent envoyer quelqu’un aggraver les gardes pour voir comment ils réagissent, et surveiller et enregistrer leur réaction. Pour tester la collusion, elle peut planter un produit (par exemple de l’or ou des pierres précieuses) et tester le contrôle d’accès des gardes pour voir s’ils confisquent le produit ou s’ils sont de connivence avec la personne qui le fait sortir en contrebande. Les contrôles de ce type sont ensuite utilisés comme scénarios d’apprentissage pour le reste de la force de garde.

Les unités d’intervention rapide sont essentielles pour faire intervenir la police, le cas échéant. Le continuum d’utilisation de la force s’applique à ces différents acteurs, la police étant l’autorité la plus élevée pour utiliser une force raisonnable.

SGA a mis au point sa propre formation, car il n’existe pas de formation standard nationale pour la sécurité privée. En ce qui concerne les droits de l’homme, l’entreprise intègre une grande partie du contenu des formations en ligne fournies par ICoCA et AGA dans ses propres formations en personne, et tous les cadres supérieurs de l’entreprise s’inscrivent eux-mêmes et suivent les cours directement.

Dans la vidéo ci-dessous, Eric Sambu, directeur général de SGA Security, Tanzanie, nous fait part de ses réflexions sur… SGA Security, les raisons pour lesquelles l’entreprise s’est jointe à ICoCA et à AGA :

SGA Security, pourquoi l’entreprise a rejoint ICoCA, l’impact que cela a eu sur l’entreprise ;

Comment l’entreprise aborde son engagement envers les normes internationales en matière de pratiques de sécurité privée ;

La façon dont l’entreprise a abordé le contrat avec AGA à GGM et les politiques, processus et pratiques qu’elle a mis en place pour institutionnaliser des pratiques de sécurité responsables dans la mine.

Eric Sambu, Directeur Général, SGA Security

Dans la vidéo ci-dessous, Joakim Sabana, directeur des opérations de SGA Security, en Tanzanie, parle:

- La formation de SGA sur l’impact des droits de l’homme sur la communauté ;

- Les différentes composantes du cadre de sécurité autour de la mine, notamment : la sécurité interne, la police, SGA Security, la police de proximité ;

- Le processus de sélection et de formation de la police de proximité ;

- La manière dont SGA établit la confiance avec la communauté environnante de la mine.

Joakim Sabana, Director of Operations, SGA Security

SGA Security – Les défis en matière de ressources humaines lors de l’exploitation d’un site distant

SGA Security a développé une fonction RH sophistiquée qui est mise en place et supervisée depuis Dar es Salaam, mais gérée localement depuis Geita. Les cadres supérieurs de l’entreprise se rendent fréquemment sur le site de la mine pour des réunions régulières avec le directeur du site et pour entendre les plaintes déposées contre l’entreprise.

- Recrutement – Des annonces sont publiées dans les médias locaux afin de sensibiliser les habitants de la région aux possibilités offertes. Les candidats sont d’abord recrutés dans la force de réserve (service national – JKU). Ensuite, d’autres critères minimaux sont pris en compte, tels que le niveau d’éducation et l’âge. À GGM, il est demandé de recruter au sein de la communauté de Geita, la même communauté que celle où se déroulera l’affectation. GGM a également demandé à SGA Security de donner la priorité au recrutement au sein de la police de proximité, dont le nombre ne cesse de croître. Cela rend les fonctions de police de proximité plus attrayantes, étant donné les perspectives de carrière que ces postes peuvent potentiellement ouvrir. SGA Security implique toutes les parties prenantes concernées, par exemple l’équipe de sécurité régionale de la force de réserve nationale est consultée pour vérifier les certificats des candidats. On estime que les droits de l’homme commencent dès le processus de recrutement : « C’est le droit d’avoir la possibilité de gagner sa vie de manière décente ». Les personnes sélectionnées le sont sur la base de leur mérite, celles qui sont écartées le sont parce qu’elles ne possèdent pas les qualifications requises. Une norme de qualité minimale est maintenue par l’équipe régionale des ressources humaines ainsi que par le responsable des ressources humaines qui se rend dans la région pour superviser le processus de recrutement. Des contrôles réguliers sont effectués par tous les membres de l’équipe de direction – avant, pendant et après le recrutement.

- Vérification des antécédents – Les candidats font l’objet d’une vérification de leurs antécédents. Il s’agit notamment d’obtenir des références auprès d’anciens employeurs, de l’équipe de sécurité régionale de la force de réserve, etc. Une vérification judiciaire est également effectuée en coopération avec le ministère de l’intérieur et la police, afin de s’assurer que le candidat n’a pas d’antécédents criminels ou d’autres signaux d’alarme. Une fois les processus internes et externes terminés, une offre est faite au candidat.

- Formation – En plus de la formation qu’ils ont reçue dans le cadre du programme JKU (9 mois ou 6 mois de formation), les gardes suivent une formation de deux semaines. Comme mentionné ci-dessus, la formation aux droits de l’homme de ICoCA a été incorporée dans les cours de formation et les manuels de formation de SGA Security. Ebenezer déclare : « ICoCA a été un partenaire formidable. Le soutien que nous avons reçu a complètement façonné l’équipe de direction et nos opérations. Aujourd’hui, demandez à n’importe quel garde ce que sont les droits de l’homme et je vous assure que vous serez surpris par les réponses que vous obtiendrez ». (voir l’entretien ci-dessous avec Edward Diswas).

- Progression de carrière – SGA Security a mis en place des plans de progression de carrière pour les agents de sécurité. Par exemple, les candidats internes se voient offrir des possibilités d’accéder à des postes plus élevés. Le responsable de la sécurité chez GGM est un bon exemple de personne dont la carrière a progressé au sein de l’entreprise. Il était gardien il y a seulement cinq ans lorsqu’il a rejoint l’entreprise. Il a été promu à un poste de direction après seulement quelques années en tant que gardien et il est aujourd’hui responsable d’environ 600 personnes.

Travailler sur un site éloigné présente des défis uniques pour les gardes, auxquels SGA Security a répondu de la manière suivante :

- Comme le site comprend des postes éloignés, l’accès au site est difficile – SGA Security organise et fournit un transport coordonné vers le site.

- En raison de l’éloignement des postes, la nourriture peut être difficile d’accès – les repas sont fournis par SGA Security à l’arrivée du personnel sur le lieu de travail.

- Le paiement des salaires peut parfois être difficile en raison de problèmes dans les systèmes bancaires en ligne – SGA Security a travaillé avec les banques pour résoudre les problèmes liés au système de paiement des salaires.

- Dans la plupart des cas, le salaire minimum n’est pas suffisant pour assurer la subsistance des gardes – SGA Security paie ses gardes au-dessus du salaire minimum.

Dans la vidéo ci-dessous, Ebenezer Kaale, responsable des ressources humaines chez SGA Security, explique comment SGA Security aborde la mise en place d’une opération de sécurité de grande envergure dans un nouveau site isolé tel que GGM.

Ebenezer Kaale, Responsable RH, SGA Security

Le rôle de SGA à GGM

Dans la vidéo ci-dessous, Dickson Webi et l’une des agentes de sécurité discutent des dispositions prises par SGA Security à GGM :

- L’interaction entre SGA Security, le programme de police de proximité, la sécurité interne de GGM et la police ;

- Les conditions de recrutement de SGA, qui comprennent la preuve de l’achèvement de la formation militaire avec JKT (formation de 9 mois) ou Mgambo (formation de 6 mois), une éducation secondaire et un âge minimum de 21 ans ;

- L’évolution de carrière ;

- le traitement et la formation du personnel.

Dickson Webi est ingénieur diplômé. Sur les 700 agents de SGA Security à GGM, 169 sont diplômés de l’université. Travailler pour SGA Security, un prestataire de services de sécurité privée responsable qui rémunère son personnel de manière équitable, offre également de réelles possibilités de carrière. En tant qu’agent de sécurité privée à GGM, ils peuvent gagner un meilleur salaire que dans beaucoup d’autres professions. En cinq ans chez SGA, Dickson est passé du statut d’agent de sécurité à la gestion d’un site de 700 personnes.

Dickson Webi, Responsable de la Sécurité du site de la Mine d’or de Geita, SGA Security

L’agent de sécurité de première ligne

Dans la vidéo ci-dessous, Edward Dismas, agent de sécurité à SGA, décrit les cadres des droits de l’homme sur lesquels il a été formé et l’impact de cette formation.

Entretien avec Edward Dismas, Responsable de la Sécurité à la Mine d’or de Geita, SGA Security

Recommandations

- Passer un contrat avec des entreprises certifiées ICoCA. Cela démontre la mise en œuvre des PVSDH et garantit une prestation de sécurité privée responsable, avec une direction engagée et une main-d’œuvre bien formée et traitée équitablement, parfaitement au fait des droits de l’homme et du droit humanitaire international.

- Recruter localement. Cela offre des opportunités de carrière à la communauté locale, renforçant davantage les relations entre le client et la communauté où il opère et contribuant à la licence sociale d’exploitation.

- Intégrer le prestataire de sécurité privée, idéalement un membre certifié de ICoCA, dans tous les dispositifs de sécurité. Cela a un impact positif sur les autres acteurs de la sécurité, les meilleures pratiques étant reproduites et les connaissances transmises tout au long de la chaîne.

- Maximiser les responsabilités des prestataires de sécurité responsables, par exemple en les autorisant à porter des armes à feu non létales, car celles-ci peuvent constituer un moyen de dissuasion important qui leur permet d’éviter de faire appel à la police.

3. La Police – Principes Volontaires sur la Sécurité et les Droits de l’Homme

Le rôle de la police à GGM est réduit au minimum, comme en témoigne son nombre réduit. On fait appel à eux pour des tâches que les autres fonctions de sécurité (sécurité interne, entreprise de sécurité privée, police de proximité) ne sont pas autorisées à effectuer, notamment la protection, l’escorte et le transport des lingots, l’arrestation, la détention et pour faire face à des situations dangereuses où une force maximale peut être nécessaire. Entre 40 et 80 policiers sont affectés au site à tout moment, en fonction de l’environnement opérationnel. La police réside dans un camp situé à l’intérieur de la concession. Leur nombre varie en fonction des besoins à un moment donné. La police et la sécurité privée se combinent lorsque les prestataires de services de sécurité privés patrouillent sur le site. La police est utilisée pour les opérations à plus haut risque, telles que le stockage du produit et les expéditions de lingots. La police porte des AK-47, mais la sécurité interne n’est pas autorisée à porter ces armes à feu. Les policiers munis d’armes létales doivent également être déployés avec un policier muni d’armes non létales, telles que des balles en caoutchouc et des gaz lacrymogènes. De cette manière, la police est en mesure de mettre en œuvre un continuum d’utilisation de la force, en augmentant progressivement sa réponse aux intrus si nécessaire, plutôt que de répondre immédiatement avec des balles réelles. La police prendrait le relais en cas d’incidents au sein de la communauté, mais cela ne s’est pas produit ces dernières années, depuis la mise en place du programme de police de proximité.

Tous les policiers employés sur le site doivent être formés à l’usage de la force et aux droits de l’homme (PVSDH). Ils effectuent des rotations de deux semaines sur le site.

La police est également étroitement impliquée dans le contrôle du personnel de sécurité privé. La police vérifie notamment les antécédents judiciaires et autres signaux d’alerte.

La police est également responsable en dernier ressort des agents de la police de proximité, y compris de leur formation.

Recommendations

- Reconnaître les contraintes de ressources dans lesquelles la police publique opère souvent et concentrer son engagement sur les tâches que les autres acteurs de la sécurité ne sont pas autorisés à effectuer.

- La police de réserve, en tant que dernière ligne de défense, doit cependant s’assurer qu’elle porte des armes à feu non létales et qu’elle est ainsi en mesure de suivre un continuum d’utilisation de la force, en utilisant toujours le minimum de force requis dans une situation donnée.

- Reconnaître le rôle essentiel de la police en l’intégrant dans le dispositif de sécurité plus large et l’impliquer dans la formation.

4. La Police de Proximité – Partie Intégrante de la Sécurité et des Relations avec la Communauté

Programme pilote et structure

Entre 2015 et 2016, un projet pilote de police de proximité a été lancé dans deux localités d’où provenaient 60 à 70 % des incursions. Le lancement du programme a été motivé par trois raisons principales :

S’attaquer à l’activité criminelle, y compris les incursions autour du site ;

Lutter contre la criminalité et les maux sociaux au sein de la communauté ;

Offrir des opportunités d’emploi aux communautés environnantes ;

Faire face aux ressources limitées et au manque de capacités de la police et soutenir la police – soutenir le renforcement des capacités des forces de l’ordre locales.

Le projet pilote au village de Nyakablae, une communauté vivant à l’intérieur de la concession avec le traitement illégal de GBM qui représentait 60% des incursions illégales à l’époque. Le programme pilote s’est déroulé de 2015/16 à 2020. Cette période de quatre ans a permis d’étudier les impacts et les lacunes du programme, laissant à l’équipe le temps d’itérer et de tester les adaptations de l’approche. La première vague de recrutement comprenait 131 policiers de proximité, qui ont été formés par une série de parties prenantes, dont la police et les agents de l’immigration, car il existe également des problèmes d’immigration illégale en provenance des pays voisins.

Le dispositif de police de proximité prévoit le recrutement de « policiers » de proximité tous les douze mois par l’intermédiaire de comités de rue, avec la participation des équipes chargées de la sécurité et de la responsabilité sociale de l’entreprise. Les comités de rue sont composés de représentants démocratiquement élus de la communauté. Le devoir de chaque comité de rue est de s’assurer qu’il protège les avantages de GGM pour la communauté qu’il représente. Il existe deux sous-comités pour chaque comité de rue : un comité de développement et un comité de sécurité et de défense. GGM apporte une contribution financière aux comités de rue, dont une partie sert à rémunérer la « police » communautaire par l’intermédiaire du comité de sécurité et de défense, le reste étant affecté au financement de programmes de développement communautaire déterminés par les comités de développement. Un comité de pilotage supervise l’équipe de police de proximité, mais les forces de police tanzaniennes conservent le contrôle final. Les GGM ont signé un protocole d’accord avec les forces de police tanzaniennes à cet égard.

La police de proximité est recrutée pour une période de douze mois seulement. Cette rotation annuelle est un élément crucial de l’accord. En revanche, d’autres mines en Tanzanie ont adopté un programme de police de proximité, dans le cadre duquel la police de proximité est recrutée pour des périodes beaucoup plus longues, allant même jusqu’à dix ans. Cependant, ce mandat prolongé peut conduire à la corruption et à la collusion, provoquant des tensions au sein de la communauté entre ceux qui ont un emploi et ceux qui n’en ont pas. Un contrat de 12 mois clairement défini, sans espoir de reconduction, permet d’éviter les pièges de l’accaparement par la communauté et empêche l’exacerbation des tensions qui peuvent résulter de la protection par les personnes de ces postes très convoités.

Les candidats au programme doivent répondre aux critères suivants :

- Être résident permanent depuis au moins cinq ans ;

- Être en bonne santé physique et mentale.

- Avoir plus de 18 ans et moins de 45 ans ou être âgé de 45 ans.

GGM propose une formation sur les principes volontaires en matière de sécurité et de droits de l’homme, ainsi qu’une formation sur la sécurité.

Rôle de la police de proximité

La police de proximité agit comme une première ligne de défense, en tant que gardiens et gardiennes postés dans les zones non actives de la concession et le long des limites de la mine, afin de surveiller et d’avertir toute personne qui s’égare dans la concession ou près du site minier actif – ils n’interviennent cependant pas activement auprès des intrus. En cas d’intrusion, la police locale informe le centre de contrôle de la sécurité. Comme il y a des caméras de surveillance stratégiquement positionnées à intervalles réguliers autour de la concession, le centre de contrôle lance les équipes d’intervention nécessaires. Ils échangent des informations sur le nombre d’intrus, l’endroit où ils sont entrés, etc. Ces informations sont ensuite traitées par le service de sécurité interne de Geita, qui prend les mesures appropriées.

Ils agissent également en tant que gardiens de la réserve forestière de Geita en effectuant des patrouilles forestières pour s’assurer qu’il n’y a pas d’activité illégale dans la zone forestière. La police communautaire sert également de collecteur d’informations au sein de la communauté, afin d’aider la police à maintenir l’ordre public.

Ils portent des combinaisons vertes en guise d’uniforme et utilisent des équipements de protection individuelle (EPI) s’ils sont affectés dans une zone qui l’exige. Ils ne sont pas armés et ne portent pas d’armes. L’un des avantages potentiels du recours à la police de proximité est qu’il y a moins de risques d’agression de la part d’intrus provenant des zones environnantes, car les policiers de proximité sont eux-mêmes membres de la communauté environnante.

La police de proximité collabore avec le prestataire de services de sécurité privée. Au moment où ce cas a été documenté, le prestataire était SGA Security, une société certifiée ICoCA.

Impact du programme

Les résultats du programme pilote de police de proximité sont clairs. Non seulement les incursions ont diminué de manière significative au cours de la phase pilote, mais les crimes commis dans la communauté, notamment les viols et les cambriolages, ont également baissé. Grâce à cela, la communauté a vu les avantages de l’initiative et l’a soutenue. Le programme de police de proximité a depuis été étendu à 15 communautés des environs, employant actuellement un total de 957 personnes en tant que police de proximité à l’intérieur et autour de la concession. Le plus grand défi pour la police de proximité est l’immensité de la zone qu’elle doit surveiller, mais elle reçoit l’aide des patrouilles de sécurité de SGA.

Comme l’indique le directeur principal de la sécurité de GGM, « on ne peut pas retirer la sécurité à la communauté. Il faut que la communauté ait le sentiment de faire partie de l’entreprise… le programme de police de proximité a donné à GGM l’autorisation sociale d’opérer ». Le programme de police de proximité a permis à GGM d’obtenir le permis social d’opérer ». En 2030, la division de la sécurité de GGM aspire à une « sécurité intégrée et renforcée par la communauté ». Le programme de police de proximité offre également d’autres possibilités aux membres de la communauté ayant reçu une formation. Certains policiers de proximité sont recrutés par des sociétés de sécurité privées, d’autres postulent à des postes dans la police publique, tandis que d’autres encore sont engagés par les autorités locales. SGA Security, le fournisseur de services de sécurité de GGM au moment de la rédaction du présent rapport, a confirmé qu’il donnait la priorité aux personnes ayant suivi le programme de police de proximité. Comme l’a déclaré le directeur principal de la sécurité de GGM, « le programme de police de proximité donne aux enfants un avant-goût du monde du travail, ce qui est important pour les aider à façonner leur vie. […] Lorsque les membres de la communauté voient l’impact de la police de proximité sur leur famille, tout le monde veut en faire partie ». La police a également confirmé que le programme de police de proximité permet aux gens d’acquérir des compétences et une éthique de travail qui leur ouvrent des perspectives d’avenir. Les salaires perçus par la police de proximité ont été utilisés par certains, dont des femmes recrutées, comme fonds d’amorçage pour lancer leur propre entreprise. Sur le groupe initial de 120 policiers de proximité, 85 ont été recrutés dans le secteur de la sécurité privée dans l’année qui a suivi la fin de leur mission.

Le programme de police de proximité est l’une des principales raisons pour lesquelles le recours à la force a considérablement diminué, et la région jouit désormais d’une paix et d’une sécurité relatives. Cela est dû en grande partie à la compréhension mutuelle qui s’est développée entre GGM et la communauté environnante en raison du sentiment d’appartenance que le programme de politique communautaire a suscité.

Domaines d’amélioration

Il y a toujours des domaines à améliorer. L’un d’entre eux pourrait être l’augmentation des salaires des agents de police de proximité. Cette mesure aurait un impact particulier sur les femmes agents de police de proximité, car les femmes ont tendance à ramener au foyer un pourcentage plus important de leur salaire que les hommes et à utiliser leurs revenus pour fournir les ressources financières nécessaires à la création de petites ou moyennes entreprises. Un autre domaine serait de créer davantage d’opportunités de carrière pour les anciens agents de la police de proximité, que ce soit dans le secteur de la sécurité privée, dans les forces de police, dans d’autres postes de l’administration locale ou même au sein de GGM.

Dans la vidéo ci-dessous, Mihinzo E Tumbo, le Surintendant de la Sécurité de GGML, partage son point de vue sur le programme de police de proximité qu’il gère.

Mihinzo E Tumbo, Directeur de la Police de Proximité, GGML

Recommandations

- Piloter l’intégration de la communauté dans les dispositifs de sécurité, laisser le temps d’itérer et de tirer des leçons avant de passer à l’échelle supérieure.

- Renforcer les structures existantes de gouvernance communautaire en intégrant la police de proximité et en la reliant au développement communautaire.

- Promouvoir la sécurité communautaire dans le double but d’améliorer la sécurité de la communauté et de l’entreprise.

5. Utilisation de la Technologie – Sécurité sans Frontières

La technologie est largement utilisée dans les composantes de sécurité et de sûreté des opérations de GGM. Au total, il y a 445 caméras de télévision en circuit fermé. La vidéosurveillance utilise des caméras thermiques haut de gamme dont la portée et la sensibilité nocturne sont impressionnantes. Par exemple, la portée des tours de vidéosurveillance peut atteindre 10 km. Cela permet de réduire la charge de travail des patrouilles, car les tours de vidéosurveillance sont placées à intervalles réguliers sur les limites du site pour permettre une surveillance étendue et une détection proactive des menaces. Des caméras de surveillance sont également utilisées dans tous les véhicules et des caméras corporelles sont en cours d’introduction pour faciliter les enquêtes en réponse à d’éventuelles allégations de violation des droits de l’homme par les agents de sécurité.

Bien qu’il n’y ait pas de frontière physique, ni de mur ou de clôture, les tours de vidéosurveillance ainsi que les balises et les rochers peints placés tous les 500 mètres dans les zones forestières et tous les 200 mètres dans les zones peuplées servent essentiellement de marqueurs de frontière (en accord avec les communautés), indiquant clairement à toute personne s’approchant de la concession où commencent les locaux de la mine. Dans les zones où des activités d’ASM sont menées, GGM a également mis en place des routes le long de la concession pour indiquer les limites. Le positionnement et la peinture des rochers eux-mêmes sont le résultat d’un projet d’engagement communautaire mené en 2012 pour sensibiliser la communauté et obtenir son accord sur les limites de la concession. À l’époque, AGA avait délibérément décidé de ne pas construire de limite (mur/clôture), car la direction de la société estimait que cela contribuerait à créer un sentiment de division entre la mine et la communauté environnante, en créant une opposition entre eux et nous. L’absence de frontière physique a contribué à l’amélioration des relations et du sentiment de confiance entre la communauté et l’entreprise. Ce processus a également été pris en compte dans le programme de police de proximité, car la police de proximité est en mesure de signaler les intrusions en enregistrant les incidents. L’accent est mis sur l’utilisation de la technologie pour améliorer l’efficacité, réduire l’intervention humaine et, en fin de compte, réduire le risque de collusion, qui est aujourd’hui le plus grand défi auquel la mine est confrontée compte tenu des améliorations significatives des relations avec la communauté.

Recommandations

- Tirer parti de la technologie pour compléter les dispositifs de sécurité physique ; la télévision en circuit fermé et d’autres outils peuvent remplacer les barrières.

- Utiliser la technologie de manière responsable, notamment pour responsabiliser les agents de sécurité, par exemple en déployant des caméras corporelles.

- Veiller à ce que la communauté environnante soit impliquée et comprenne comment les outils technologiques sont déployés sur le site.

6. RSE – Investissement dans la Communauté

Les initiatives de GGML en matière de RSE s’efforcent d’être bénéfiques à la société et à l’environnement, conformément aux valeurs de l’entreprise, qui incluent la transformation des communautés en un développement durable autonome. L’éthique du programme RSE est que la présence de la mine profite aux communautés environnantes.

La mine met en œuvre des projets de RSE depuis sa création en 2000 et a dépensé plus de 100 milliards de Tsh (environ 39 millions de dollars) dans les domaines de l’art et de la culture, du développement économique et social, des infrastructures, de l’éducation, de la santé, de l’environnement et du développement des petites et moyennes entreprises. En 2017, le gouvernement tanzanien a introduit la loi sur la RSE dans le cadre de la loi sur les mines (Mining Act 2010, Miscellaneous Amendments 2017), section 105. En 2023, le gouvernement tanzanien a également publié une ligne directrice sur la RSE dans le but de réglementer les activités de RSE conformément à la loi sur l’exploitation minière. Depuis 2018, la mine a investi plus de 55 milliards de shillings tanzaniens (environ 21 millions de dollars) dans le développement communautaire.

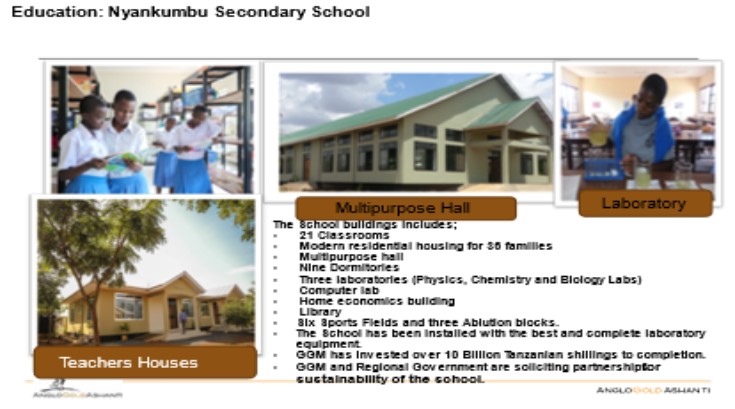

Plus de 1300 projets ont été mis en œuvre entre 2018-2023, y compris la construction complète et la rénovation d’écoles, la construction d’installations sanitaires, des projets générateurs de revenus, la jeunesse, les sports et la culture, pour n’en citer que quelques-uns. Avant 2018, la mine a construit et lancé l’école secondaire pour filles de Nyankumbu, le projet Magogo d’autonomisation des femmes et des jeunes, la rénovation de l’hôpital de référence de Geita, la construction de la station de radio communautaire et du poste de police de Nyakabale et la rénovation de la prison de Geita. La mine a également construit le centre d’orphelinat Moyo wa Huruma, qui continue de bénéficier du soutien de la mine à ce jour. Le projet d’adduction d’eau de Geita, qui continue à ce jour d’assurer l’accès à l’eau des communautés, mérite également d’être mentionné.

ÉDUCATION

Depuis 2000 et dans le cadre de la loi sur la RSE introduite en 2017, 1220 projets d’infrastructure liés à l’éducation ont été menés à bien dans des écoles primaires et secondaires. Cela comprend la toiture, la construction complète d’écoles, des salles de classe supplémentaires, la construction de logements pour le personnel, d’installations sanitaires, de réfectoires et plus encore. En outre, plus de 18,000 chaises et bureaux scolaires et 700 dortoirs à deux étages ont été fabriqués et distribués aux écoles de Geita Town et Geita District Councils.

La construction de l’école secondaire pour filles de Nyankumbu reste l’un des principaux projets de Geita. L’école a été construite et inaugurée en 2014, avec divers soutiens et mises à niveau à ce jour, pour un coût de 15 milliards de Tsh (environ 5 millions de dollars). Les activités de construction comprenaient 21 salles de classe, des logements modernes pour 38 familles, une salle polyvalente, neuf dortoirs, trois laboratoires et l’équipement associé, un laboratoire informatique, un bâtiment d’économie domestique, une bibliothèque, six terrains de sport et trois blocs sanitaires. L’école accueille 1100 élèves et est devenue une école prestigieuse dans la ville de Geita en raison de son bon environnement d’apprentissage et de ses performances.

SANTÉ

Plus de 150 projets liés à la santé ont été mis en œuvre pour promouvoir et soutenir l’accès à des soins de santé de qualité. Il s’agit notamment de la rénovation d’établissements de santé, de la construction de dispensaires et de bâtiments pour les consultations externes, de la couverture et de l’achèvement de projets lancés par la communauté, de logements pour le personnel, de centres de soins de santé reproductive pour les enfants, de salles pour les patients, ainsi que de l’achat d’équipements médicaux pour les différents établissements de santé. Une aide a également été apportée pour l’achat d’ambulances et le soutien aux personnes atteintes de maladies transmissibles.

DÉVELOPPEMENT ÉCONOMIQUE ET AGRICULTURE

GGML a mis en œuvre divers projets générateurs de revenus afin de promouvoir le développement économique et des moyens de subsistance alternatifs. La mine a lancé le projet de riziculture dans le village de Saragulwa et a construit des usines de production d’huile de tournesol à Kasota, Bulela et Bunegezi et a distribué des graines de tournesol à 7 000 agriculteurs (dont 1967 femmes). La construction des cadres du marché principal de Geita, qui sert de centre économique, a commencé avec les deux premières des trois phases achevées.

PROJETS D’INFRASTRUCTURES ROUTIÈRES PUBLIQUES

Au cours des dernières années, GGML a contribué à la construction et à la rénovation des infrastructures routières publiques qui permettent d’améliorer le transport des personnes, l’accessibilité et, en fin de compte, la croissance économique. Ce soutien s’est traduit par la construction de routes goudronnées (casernes de Sirro, marché de Katundu et routes goudronnées du bureau régional) ainsi que par l’installation de lampadaires à énergie solaire dans la ville de Geita. La mine a également achevé la construction des ponceaux de Nyawilimilwa et de Nyakaduha, ainsi que la remise en état de la route de Geita Bukoli et le lancement de la construction d’une route goudronnée reliée à la route principale Geita-Mwanza. Des améliorations ont également été apportées à la route d’accès à la vente aux enchères de bétail de Katoro et à la construction du pont de Nyakabale afin de favoriser la mobilité et l’accès des communautés.

7. Culture d’entreprise – Alignement sur les Valeurs

AGA est une entreprise fondée sur des valeurs, dont la première est le respect de la sécurité, qui exige le plus grand respect des droits de l’homme et la collaboration entre toutes les parties prenantes.

AGA s’est fixé cinq grands axes stratégiques, dont le premier consiste à donner la priorité aux personnes, à la santé, à la sécurité et à la durabilité. Selon AGA, « ce domaine d’action est le fondement de notre activité et de notre stratégie, garantissant l’alignement entre nos valeurs et nos responsabilités en matière de citoyenneté d’entreprise, d’une part, et la croissance à long terme, la durabilité et la rentabilité de l’entreprise, d’autre part ». Les valeurs d’AGA et la priorité stratégique qu’elle accorde aux personnes, à la santé, à la sécurité et au développement durable sont évidentes sur les panneaux d’affichage du site et dans les conversations avec le personnel.

Le modèle d’entreprise qu’AGA a développé pour mettre en œuvre son plan stratégique comprend six domaines d’intervention. Trois d’entre eux sont étroitement liés aux valeurs d’AGA et sont évidents dans le dispositif de sécurité intégré de GGM. Cette culture d’entreprise se retrouve également dans le choix du prestataire de services de sécurité privée, SGA Security. En tant qu’entreprise membre certifiée d’ICoCA, SGA Security n’est pas le fournisseur de sécurité le moins cher que GGM aurait pu choisir. Cependant, GGM a pris la décision d’investir dans un prestataire de services de sécurité qui défend les mêmes valeurs que l’entreprise, notamment en versant un salaire équitable, en contrôlant et en formant correctement son personnel, en respectant les droits de l’homme et en fournissant un environnement de travail professionnel offrant des possibilités d’évolution. SGA Security paie plus que le salaire minimum, un emploi dans l’entreprise à GGM est un poste recherché. Ce que SGA Security et AGA ont bien compris, c’est qu’un agent de sécurité heureux, en bonne santé, payé à un juste salaire et respecté par l’employeur et son client, est beaucoup moins susceptible de s’associer à des membres de la communauté ou à des employés de la mine pour voler des biens de l’entreprise. Le risque de perdre son emploi est trop élevé.

GGM et SGA Security investissent dans le capital humain en recrutant et en promouvant des personnes très compétentes issues de la communauté de Geita. Cet investissement s’étend au programme de police de proximité. En offrant de bonnes perspectives de carrière par ces voies, cet investissement se traduit par un capital social. Le programme de police de proximité en est un excellent exemple. En intégrant la communauté dans l’appareil de sécurité, GGM est allée au-delà de l’instauration d’une confiance avec la communauté, en intégrant plutôt la communauté dans le modèle d’entreprise lui-même. En s’engageant dans des cadres internationaux tels que les PVSDH et ICoCA, GGM a intégré des cadres de gouvernance et des systèmes de gestion solides, y compris des systèmes de gestion des risques, par exemple en sélectionnant une entreprise de sécurité privée certifiée ICoCA, telle que SGA Security, qui a obtenu plusieurs normes ISO, dont ISO 18788. L’utilisation intelligente de la technologie dans l’ensemble du dispositif de sécurité optimise également l’efficacité sur le site, permettant une réponse rapide et évitant l’escalade de situations complexes.

Éléments clés du modèle d’entreprise d’AGA – avec l’aimable autorisation d’AngloGold Ashanti

Recommandations

- Aligner les valeurs de l’entreprise sur le respect des droits de l’homme et la sécurité responsable.

- Aligner tous les éléments du dispositif de sécurité sur les valeurs de l’entreprise.

- Sélectionner un prestataire de services de sécurité privée qui s’aligne sur les valeurs de l’entreprise.

Conclusion

Le dispositif de sécurité innovant et intégré de GGM est un modèle instructif dont d’autres sites miniers, ainsi que des sites impliquant l’accès à la terre et aux ressources de manière plus générale, pourraient tirer des leçons utiles. Si ICoCA ne suggère pas une approche à l’emporte-pièce pour résoudre les problèmes de sécurité persistants ou pour mettre en place de nouvelles opérations de sécurité, le modèle de Geita contient néanmoins des caractéristiques qui pourraient être transférées efficacement dans d’autres contextes. Les éléments clés, sans ordre particulier, sont les suivants

- une approche fondée sur les valeurs, menée par la direction, qui place le respect des droits de l’homme au centre de ses préoccupations et qui s’étend à l’ensemble de l’entreprise et de ses chaînes de valeur ;

-une mise en œuvre démontrée de cette approche dans la passation de marchés avec des prestataires de sécurité privée responsables qui sont membres d’ICoCA ; - construire une entreprise qui implique et bénéficie à la communauté au cœur de son activité, non seulement en investissant dans des programmes de RSE significatifs, mais aussi en intégrant la communauté dans son dispositif de sécurité plus large ;

- une approche de la sécurité à plusieurs niveaux, offrant des actions et des acteurs alternatifs pour l’escalade, y compris le long du continuum de l’utilisation de la force, dont beaucoup peuvent être directement influencés par la culture de l’entreprise, y compris le respect des droits de l’homme, évitant ainsi une dépendance excessive à l’égard de la sécurité publique, qui peut ne pas être aussi encline ou aussi expérimentée dans le déploiement de compétences douces ou l’utilisation minimale de la force lorsqu’il s’agit de traiter avec des intrus.

- une volonté d’essayer des approches peu orthodoxes, en jetant aux orties le manuel de sécurité traditionnel, qui rejette la sécurité comme une tâche discrète et limitée, au profit d’une approche intégrée dans l’ensemble des opérations de l’entreprise et qui inclut la communauté environnante dans son ensemble.