ESCOBAL MINE: VIOLENT REPRESSION OF INDIGENOUS PROTESTS

Escobal Mine: A History of Protests Culminating in a Shooting, a Lawsuit, a Settlement, and a Public Apology

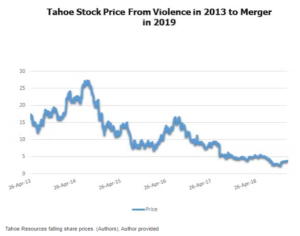

Amidst protests arising from community disapproval of Tahoe Resources’ Escobal Mine project in Guatemala, several locals of the San Rafael las Flores were allegedly shot by security personnel employed by the mine. Litigation ensued, and the plaintiffs successfully moved the lawsuit to British Columbia from Guatemala. As litigation continued, Tahoe Resources’ stock price dramatically dropped, the mine operations were suspended, and the Tahoe Resources’ successor, Pan American Silver, settled with the plaintiffs and issued a public apology

Keywords: extractive industry, weapons, clash with locals

Background

The Escobal Mine, operated by Tahoe Resources Inc. at the time of the incident, was a Canadian-owned mine in San Rafael las Flores, Guatemala. The Escobal mine produces concentrates of silver, gold, lead, and zinc. The population of the Department of Santa Rosa, where San Rafael las Flores is located, is mostly mestizo with about 5% of the population identifying as indigenous Xinka.

According to the Centro de Acción Legal-Ambiental y Social de Guatemala, the San Rafael las Flores community has rejected the Escobal Mine Project for several reasons: These reasons include the alleged threat of the project to the area’s hydrological resources, risk of other environmental impacts, and the lack of a community consultation about the mine. Allegedly, prior to the incident, over 500 members of the local communities gathered to protest at the mine, demanding that the company workers leave the area.

The Incident

On April 27, 2013, members of the community, including the Plaintiffs-Appellants in the case, participated in a protest outside the gates of the mine. According to information discovered during the course of the litigation, Tahoe’s security manager, Alberto Rotondo Dall´Orso, was concerned that the protests would interfere with the operation of the mine. This belief arose out of prior conflicts resulting from protests of the mine; the security and Tahoe Resources personnel were allegedly aware of the strong community opposition to the mine project.

The Plaintiffs-Appellants alleged that security guards then opened the mine gates and “opened fire on the protestors using weapons that included shotguns, pepper spray, buckshot and rubber bullets.” Several protestors were injured.

Finally, the Plaintiffs-Appellants alleged that the shooting was planned, ordered, and directed by Rotondo and that Tahoe “expressly or implicitly authorised the use of excessive force by Rotondo and other security personnel, or was negligent in failing to prevent Rotondo and other security personnel from using excessive force.”

Legal Aspects

Court cases: Garcia v. Tahoe Resources Inc., 2017 BCCA 39.

Initially, the community litigants (hereinafter, “Plaintiff-Appellants”), filed a civil claim against Tahoe Resources in the Supreme Court of British Columbia. The Appellants alleged three causes of action against Tahoe Resources: (1) direct liability for battery, (2) vicarious liability for battery, and (3) negligence. Essentially, the Plaintiff-Appellants claimed that Tahoe expressly or implicitly authorised the unlawful conduct of Rotondo and the security personnel, and as the parent company of Minera San Rafael, Tahoe Resources was vicariously liable for the battery. Finally, the Plaintiff-Appellants alleged that Tahoe had a duty of care towards the Plaintiffs-Appellants because it controlled operations of the mine, and knew about the opposition of the mine. According to the Plaintiff-Appellants, Tahoe Resources breached this duty of care by failing to conduct background checks, failing to establish and enforce clear rules of engagement, and failing to adhere to and monitor adherence to Corporate Social Responsibility policies.

In August 2014, Tahoe Resources filed a notice of application to move the proceedings to Guatemala, which the judge granted. The judge found that Guatemala was “clearly the more appropriate forum for determination of the matters in dispute.” This finding was based on the fact that the alleged battery and breaches of duty occurred in Guatemala, and that corruption within the Guatemalan criminal justice system was not relevant to the civil claims for injury.

The Plaintiff-Appellants appealed this decision, and the appellate judge agreed in 2017 that Guatemala was not the appropriate forum for the dispute. The Canadian case Club Resorts Ltd v Van Breda, 2012 SCC 17 states that context-specific factors and concerns may be considered by the court in deciding whether to apply forum non conveniens. In overturning the initial non conveniens decision, the appellate judge considered the difference in available discovery procedures in Guatemala and British Columbia, the difference in limitation period for parties to commence a civil suit, and the risk of unfairness in the Guatemalan Justice System. As these factors, according to the judge, unfairly disadvantaged the Appellants, the lawsuit was moved to British Columbia.

The International Code of Conduct

The International Code of Conduct requires that Personnel of Member and Affiliate companies take all reasonable steps to avoid the use of force, and if force is used, it should be proportionate to the threat and appropriate to the situation. (Rules for the Use of Force: paragraph 29, Use of Force: paragraph 30-32).

The Code requires stringent selection and vetting of personnel, assessment of performance and duties (paragraphs 45 to 49), and training of personnel of the Code and relevant international law, including human rights and international criminal law (paragraph 55). Meeting the requirements of the Code of Conduct, can help private security companies and their clients ensure that private security personnel are qualified, trained, supported, informed, and responsible.

Meeting the requirements of the Code of Conduct can help private security companies and their clients ensure that private security personnel are qualified, trained, supported, informed, and responsible.

Impact

Suspension of licence

In 2017, the Guatemalan Supreme Court of Justice temporarily suspended Tahoe Resources’ mining licences, until a suit against the Ministry of Energy and Mines is resolved for discrimination and lack of prior consultation with the indigenous Xinka communities. The suspended licences included the licence to operate in the Escobal Mine.

As of September 2018, the licence was still suspended. Tahoe’s Escobal mine license to remain suspended — Guatemalan court – Business & Human Rights Resource Centre

As of April 2022, Pan American Silver still had no concrete date for the reopening of the mine. Mining firms cautious as Guatemala seeks to lift suspensions – BNamericas

SettlementsPan American Silver, who had acquired Tahoe Resources earlier in 2019, settled with the Plaintiffs-Appellants to end the litigation in British Columbia in July 2019. The terms of the settlement are confidential.

Stock Prices

Tahoe Resources’ stock, prior to the incident, was priced at $27 a share, but the value fell after details of the incident at Escobal Mine emerged. The mine was eventually suspended by a Guatemalan Court, and Tahoe was sold to Pan American Silver for $5 a share.

After Pan American Silver purchased Tahoe Resources, it initiated a plan to hire more women security guards. (see p. 96, 2021 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT | Pan American Silver)

Public relations

After the conclusion of the case in 2019, Pan American Silver, a company that acquired Tahoe Resources earlier that year, released a public statement acknowledging that the 2013 shooting infringed the human rights of the protests. In the statement, Pan American Silver, on behalf of Tahoe, apologised to the “victims and the community.”

Discussion

After Pan American Silver purchased Tahoe Resources, it initiated a plan to hire more women security guards. How might an increased female security personnel presence improve community relations?

Before the incident, it was alleged that Tahoe’s security manager was concerned that the protests would interfere with the operation of the mine. How could personnel training and procedures address both the protests and the operation of the mine?

Related incidents

- Racist Murder by Supermarket Guards

- Violent Repelling of Illegal Miners Leading to Litigation

- The Nisour Square Massacre

- Repression of the Protests Against the Rio Blanco Mine

- Migration Detention Riots at Manus Island

- Violence and Sexual Assaults at Kakuzi Farms

Sources

- Commentary: Indigenous peoples are defending their rights in court—and winning

- Appeal From Order Granting Application for Stay

- Rocked: Canadian mining companies deal with fallout from Supreme Court ruling – BCBusiness

- Investors are increasingly shunning mining companies that violate human rights

- García v. Tahoe Resources Inc. – Global Freedom of Expression.

- Big win for foreign plaintiffs as Pan American settles Guatemala mine case | Financial Post

- For Tahoe Resources, Guatemala troubles underscore tense outlook | Reuters

- Tahoe Resources lawsuit (re Guatemala)

- Tahoe Resources Inc.: Exhibit 99.1 – Filed by newsfilecorp.com

- Guatemala: Community statement on recent violence at San Rafael Las Flores

- Thousands march in protest of Escobal Mine and in support of Xinca People’s right to self-determination

- Criminalization of Protest in San Rafael Las Flores to Impose El Escobal Mining Project

- Indigenous Xinka march in Guatemala to banish Canadian mine | Canada’s National Observer: News & Analysis

- 2021 SUSTAINABILITY REPORT | Pan American Silver

Case prepared by Madison Zeeman

Descargo de responsabilidad

De acuerdo con la cláusula de exención de responsabilidad de la página de inicio, ni la Asociación del Código de Conducta Internacional ni ninguno de los autores pueden identificarse con las opiniones expresadas en el texto o las fuentes incluidas en «Defender la Seguridad Responsable: El Mapa de Casos del Código Internacional de Conducta».